Sultry nights are upon us, and they evoke memories of dense movie dramas played out in dim or stark-contrast lighting, shady characters limned among the shadows of buildings, full of flashbacks, with damsels reaching out in distress and then disappearing mysteriously, and a lone hero dealing with more twists than Chubby Checker. According to Brittanica.com, film noir identifies movies containing conspiracy and cynicism, spawned by the pessimism and disillusionment of the 1930s and spurred by the unrest of a world at war in the early 1940s. What are the best flicks to turn to for mystery and suspense on the hot summer nights ahead?

Probably the most familiar example of film noir comes from director John Huston in 1941’s The Maltese Falcon. Sardonic gumshoe Sam Spade, played by Humphrey Bogart and from the pen of Dashiell Hammett, encounters a beautiful damsel in distress who then—of course!—disappears. Spade juggles carved birds and hypodermics with movie greats Mary Astor, Peter Lorre, and Sydney Greenstreet. Have your remote handy at the finale to listen carefully as each player argues for the biggest amount of money and the least amount of blame.

Bogart also breathed life into Philip Marlowe, a Raymond Chandler character in a novel from 1939, designed as an honest upholder of justice in a world gone lugubriously distrustful. Howard Hawks’ 1946 film version of The Big Sleep also starred Bogey and his favorite costar and wife, Lauren Bacall, who played opposite him four times. The movie was pre-released in 1944 before the final cut; the public far preferred the latter for the chemistry between Bogie and Bacall even though the plot came through as more complicated.

We meet Marlowe again in Farewell, My Lovely, a Chandler novel brought to the silver screen three times in total. It featured Dick Powell instead of Bogart in the first, 1942 version released as Murder, My Sweet. In 1975 we had a version with the right title costarring an aging Robert Mitchum with Charlotte Rampling. It’s an undulating tale of missing people and missing jewelry.

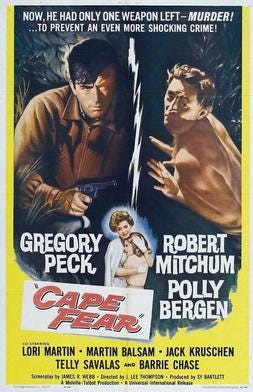

Robert Mitchum starred in a few “films noir” on his own besides Farewell, My Lovely. Among the best is Cape Fear, adapted from a John D. MacDonald novel The Executioner, about a man named Max Cady who has completed his prison sentence and decides to harass the trial prosecutor who possibly suppressed a piece of evidence that could have exonerated him. In the 1962 version directed by J. Lee Thompson, Gregory Peck played the prosecutor with Polly Bergen as his unsuspecting wife and Martin Balsam as a private eye. Peck, Mitchum, and Balsam all had roles in Martin Scorsese’s 1991 version, which featured an ominous Robert DeNiro as Cady with Nick Nolte and Jessica Lange as the hapless prosecutor and his wife. Critics have acclaimed both films, noting some greater film noir influences in the earlier version, but with both equally mesmerizing.

Mitchum also starred in David Grubb’s filmed novel Night of the Hunter, directed by Charles Laughton in 1955, about the Reverend Harry Powell, bound and determined—with LOVE tattooed on the knuckles of one hand and HATE across the other—to learn the whereabouts of a dead man’s fortune. Lillian Gish and Shelley Winters joined him in this tense thriller.

Try letting Ernest Laszlo lead you down the road in his 1950 film D.O.A., featuring Edmund O’Brien, about a man who has been poisoned by a radioactive material and goes to the police before he dies. Classic elements included, of course, the lighting and style, establishing the targeted character at the outset, flashbacks, and the cynicism that ultimately shaded the story. This early version was extraordinarily successful among critics and audiences, but a subsequent 1988 version starring Dennis Quaid, much as I love Quaid, just didn’t cut it.

Some critics consider Hitchcock’s films as expert examples of film noir—such as 1941’s Suspicion—while others insist that they’re suspenseful but not noir. In Suspicion, we certainly have the suspense, the atmosphere, and the beautiful innocent woman (Joan Fontaine) who marries—who? A hopeless romantic who cherishes her? Or a focused killer who just wants her for her money? Incidentally, Fontaine played the title role in Hitchcock’s Rebecca one year earlier and was nominated for an Oscar; for Suspicion, she won.

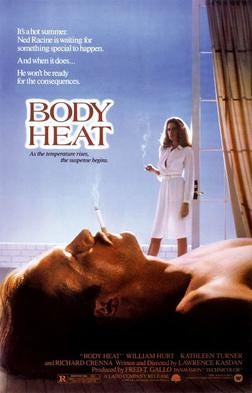

Double Indemnity was the 1944 brainchild of director Billy Wilder, who co-wrote the script with Raymond Chandler based on a novella by James Cain. Fred MacMurray is a salesman who reminds a client’s wife that he must renew his life insurance. The wife (Barbara Stanwyck) then pulls him into a scheme to insure the man and then murder him, thus triggering a double-indemnity clause in the insurance policy. The same story was used for 1981’s Body Heat directed by Laurence Kasdan, who was then a young and upcoming director using classic noir techniques as well as young and upcoming William Hurt and Kathleen Turner—who wowed audiences with their steamy love scenes.

Film noir after the 1940s has been called neo-noir, and John Huston came full circle, from directing The Maltese Falcon in 1941, all the way to 1974’s Chinatown, playing Fay Dunaway’s monstrous father, and opposite Jack Nicholson.

Here’s standard preparation for film noir: Plan on two movies. Ease up on the A/C. Turn on the overhead fan, or better yet use a stylin’ hand fan. Chill two glasses in the fridge and dip the rims in chocolate; mix up a couple of Mississippi Mudslides. Pick up some macarons at Legacy Village. Grab a partner to watch with, or drink both Mudslides yourself. You can also follow-up with my piece on neo-noir, the genre that took film noir into the 1950s and beyond.

This article first appeared in Braegen of ECOM